Last summer, a critical “cultural exchange” led to another kind of unexpected trajectory, meeting Italians in the hutong, meeting 1,500 bricks, all the serendipitous occasions* to generate a certain interest in something as random as the building block, parts and parcel, production and pieces. If we should start from the elementary, we come upon the city, piles in preparation, rubble. It’s a deception, that solidity, for things break and fall apart as much as they are constructed. Such temporalities come fired here in coal burning kilns—in both an economic and an environmental sense a dangerous consideration of only the momentary—things are just not built to last. Our building block seems more a blockade than an independent solidity, less object (or part thereof), but a conjunctive to be considered alongside the motion around it: the brick is door stop and speed bump and chalk all in one. Solidity delineates, separates, blocks, protects and becomes an object of relation. Then add sticky rice, and we’ve got all the time in the world.

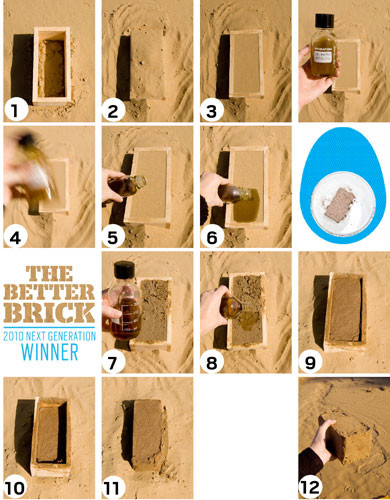

Mud brick by Stephanie Shepherd

Mud brick by Stephanie Shepherd

Artists Stephanie Shepherd and Barbara Balfour recently came by HomeShop and we happened to stumble upon our common interest in sticky rice and bricks, though Stephanie has taken it to a critical experimental level, self-concocting her own re-mixture of an ancient technique involving a sticky rice mortar (found dating back to the North-South Dynasty, 386-589) to attempt an ultra durable block similar to those found as parking markers all over the city. A thousand year old blockade, a point which we would be invited to keep coming back to again and again. To delineate or separate, block or protect, to become an object of relation. These are continuities more than divisions as we might have first thought, the building blocks of an imagination for another time-sense.

from the series “Behind the Restaurant”, by Barbara Balfour

from the series “Behind the Restaurant”, by Barbara Balfour

Would it be possible to say the same for something non-created, or to ask further, what forms of imagination take place in a way of seeing? Barbara’s series of photographs of the backside of the Tuanjiehu branch of Beijing’s famous 大董 Dadong Roast Duck restaurant take on a similar time quality, though here solidity comes in the form of constancy and routine. Continuities embed themselves in the daily processes behind, outside of and next to the restaurant’s main activities of cooking and eating. People enter in and out, make and receive deliveries, take inventory, line up for staff meetings, take smoke breaks. While the camera maintains a fairly fixed position from her apartment window, the frame is searching, zooming in or out and moving somehow relative to all the action below, an object of relation.

时间 posted on: 18 June 2010 |

时间 posted on: 18 June 2010 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under:

[photo by 高灵 Gao Ling]

[photo by 高灵 Gao Ling] [photo by fotini lazaridou-hatzigoga]

[photo by fotini lazaridou-hatzigoga]