This text was originally written in 2011 for 艺术世界 Art World magazine and quietly rejected, left as random thoughts in my computer somewhere, dusty. But recent considerations of performance for a few upcoming activities at HomeShop led me to do a bit of copy-pasting here now, one year later, just a thought.

—-

.黎巴嫩贝鲁特市 Beirut, Lebanon. April 2011.

I’m not entirely sure whether he directed his garbled shouting at us especially for the sake of our foreignness, or if perhaps he slurs that cocktail of memory, pride and political anger in all directions all the time, but anyhow, that afternoon my companions and I happened to serve well as the fresh, naîve ears to stop and pay him attention. He sat in a wooden chair on a street corner in the middle of the Armenian neighbourhood of Beirut, and a little girl wearing a bubblegum-coloured sweater and two fluffy pink decorated pigtails stood tucked into the embrace of his wildly gesticulating presence.

He caught sight of us quickly and beckoned us over; she seemed completely indifferent except for the potato chips that inspired her slow repeated movements from the bag to her mouth. Next to them was a covered 三轮车 three-wheel cart with a black plastic bag on top of it. Not really to hide anything, probably mostly out of convenience, the bag contained one bottle of water and one bottle of Johnnie Walker Red Label. Most conveniently, just within his arm’s reach stood a full glass of Klashinkof’s (pronounced like the gun) afternoon aperitif.

Despite his broken English, Klashinkof’s words shot out quickly and fiercely as his name implied, and the little war created by this ranting scene was made all the more extreme by the slow-motion softness of a round-faced little girl eating potato chips and a white cat with one blue eye and the other green, circling around them stealthily like a protective friend or a too-obvious spy.

Over the course of a few minutes, Klashinkof’s banter jumped from colourful quips about the nature of human life (“In the world there is two kinds of holes: you come out from your mother, and the next one, you go down. Two holes.“) to nostalgia over his acting days, Lebanese politics and religious jokes. We find out later that Klashinkof is known by many Beirutis already, his notoriety extending much further than the small radius of this little corner in the Bourj Hammoud area where he lives, works (mafia turned actor turned fish vendor, apparently) and drinks. A friend who also lives in the neighbourhood describes him as “a bold man—fearless, crazy, a specimen of what could be left from the times when Lebanon was full of fearless militias who could talk freely and yell in their own street and region. [The only difference is that] he doesn’t carry a gun anymore. But his hair is still combed back with gel typical of a street boy who tries to seduce women.”

Of course Klashinkof is a performer. And our fascination with him as visitors in an unfamiliar neighbourhood stems at least in part from his ability to attract our attention with his charisma, extravagance and extremity. On an everyday corner in an everyday neighbourhood, we find just a little bit of craziness. And that’s always memorable, now isn’t it?

Why is it that we always tend to forget the banal and remember the extravagant? This cannot be an entirely true statement, of course, because otherwise we would not even be able to remember routines, the people we see on a daily basis or even the days of the week. Both are considered long-term memory, but there is a strong distinction in their qualities, of which cognitive scientists classify as either procedural memory (eg., habits and learned skills like reading or bicycle riding) or declarative (memories that must be cognitively recalled, and can be spoken or written about). We could say that procedural memory may generally describe those banal forms of long-term memory in that they are repetitive and, therefore, carry less emotion in their recollection. Declarative memory, however is often highly implicated with emotion (studies show that thematically induced emotional stimuli aid in the memory of events), and going back to Klashinkof, it’s no wonder that his passionate sentiments were able to carve a strong memory for me and my companions.

.中国北京市 Beijing, China. June 2011.

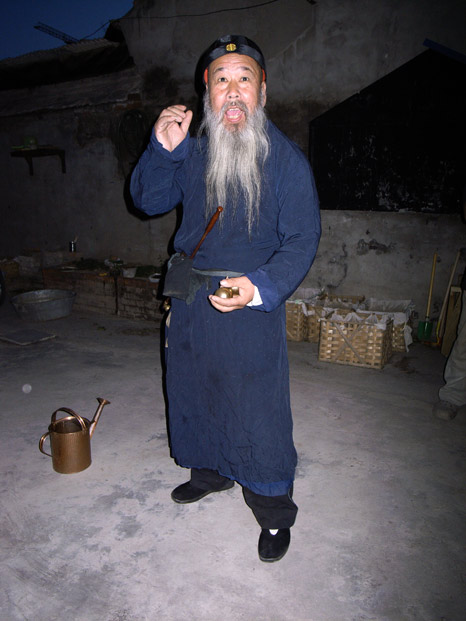

长胡子叔叔在2011年夏天的日历餐厅做表演。Uncle Longbeard performs at the Calendar Restaurant, Summer 2011.

Back in the place where I live—which on a scale of memorability probably ranks much higher in the banality of procedural activities rather than the declarative, there is another old man who excels at shouting out in the streets, though this man does it for a living rather than out of a disgruntled attitude. Uncle Longbeard is a performer of his own culture, and he 吼卖 calls out old Beijing vendors’ songs not because he is selling anything in particular, but because he performs his own culture as an old Beijinger. He does this for money even, working at Temple Fairs and famous tea houses, but when he spontaneously comes over and sings in our courtyard for us, it is immediately obvious to whom this performance is memorable and to whom it is not. We either eat it up, feeling that authenticity has stumbled upon us, or are merely slightly amused and quickly grow inattentive. Here, what is ‘normal’, at least in terms of its familiarity with our own histories, is not worthy of the space it takes up in our brain storage, but what is ‘exceptional’ delights and leaves a strong impression.

In much the same way, our reactions to Klashinkof were much stronger than those that live in the same neighbourhood and hear his same stories everyday, but what is crucial to note here is that there is a blurry realm in between the synapses of memory, where emotion and familiarity affect our abilities to identify and recall. What happens, then, for our considerations of identity itself? We can say that identity is built from a full spectrum of memories, from the inherited ones of biology (the memory of genes) to those of society (eg., education and cultural memory). And while certain determinants of our identity may be fixed or unavoidable, like race or the social class into which we are born, what should be more carefully considered is the precarity that most of these determinants are really founded upon. To say that one is “Chinese” even, carries a myriad of complex tones and meanings depending upon one’s own associations with the concept of Chineseness. Thus our representations of any such identity can only ever be the playing out of ideas about that concept, whether or not we consciously do it, like Uncle Longbeard, or perhaps just uncontrollably express, like a wildly gesticulating drunk Armenian on a street corner in Lebanon. Judith Butler’s seminal work on gender claims that “identity is performatively constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its results”, and the very idea of an expression occurs cognitively at the realm of the symbolic, no matter how clear the links may be or not. These symbols, taken in juxtaposition with human memory, become suddenly much more fallible, subjective constructions than the solidity we may have imagined from abstractions such as “male”, “female”, “Chinese” or even “high-class”. Of course, such ideas are long accrued concepts that stay well bolted into long-term memory, so their flexibility cannot come without a great deal of hitting against the norms of society. And we can never really opt-out of the performance of our identities, so to speak. Uncle Longbeard and Klashinkof are two players of a dying breed, whether of an old Beijing or an old Armenia. They’ve performed their roles so long there is no longer any distinction between performance and history. And that playfulness, or ambiguity, is perhaps something to consider.

时间 posted on: 1 June 2012 |

时间 posted on: 1 June 2012 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: