On the Problem of Transplantation

Julie Ren (julie.ren@hu-berlin.de) visited HomeShop in 2012 and spoke with Elaine W. Ho and Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga about the various issues around initiating and sustaining art/project spaces in Beijing and Berlin for her Humboldt University dissertation research. While gentrification is not her area of research, it is something she is trying to approach critically, especially as a dominant framing of urban change. In preparation for an upcoming publication on the topic, she continued the discussion with Michael Eddy.

Julie: I’m still doubtful about applying the gentrification lens to Beijing, and I plan to focus my contribution to the book on the problems of transplanting urban concepts. To me, it’s a hermeneutic lens and it reflects the need to interpret urban change in terms of dominant academic canons—whether it’s global/mega cities, cosmopolitanism, network societies, mobility paradigms… or gentrification.

My doubt is two-fold. First, I’m skeptical about its being an accurate means to interpret the socio-economic and demographic changes in Beijing neighborhoods. Sure, many neighborhoods are visibly changed, there is high turnover of residents and prices are increasing. But is this the result of an urban gentry moving in to displace residents with a lower average income? With a view to neighborhoods such as Gulou and Wudaoying within the 2nd ring, this seems more a top-down business development scheme rather than a residential real estate-driven change. Especially in the Hutongs, I wonder about the issue of demographic change – to what extent is it income and to what extent is it elder residents being replaced with younger residents? To what extent are they being displaced, and to what extent are Hutong residents moving out to become new landlords?

Secondly, I’m concerned about the embedded normative question of: Should we interpret urban change in Beijing in terms of gentrification? As I stated above, I think it’s a hermeneutic instrument that reflects the academic background and experiences of those seeking to understand urban change in Beijing. Moreover, there are assumed notions of urban inequality and social justice accompanying the term that allude to the realities of a neoliberal city in which mobility and privilege often function in tandem. Yet mobility in Chinese cities is a fraught issue, often a result of broad macroeconomic changes driving rural poor to find work in cities, exacerbated by remittance obligations and a lack of legal status. (A much more pressing issue of urban inequality might be Hukou reform rather than neighborhood-level change.)

It just seems to me there are fundamental assumptions about gentrification that fail to account for the realities of the urban context in Beijing. I can understand why especially the growing international community in Beijing might be thinking in these terms, but I wonder if it doesn’t have more to do with them, than the city in which they live?

Michael: As for your first doubt, it is well-founded. However, I wonder where you can draw the line between the good-intentioned BoBos and top-down gentrification, even in Beijing. If you think of the Richard Florida school of thought and the thousand waterfront loft conversions and creative districtings it inspired toward the “creative cities” obsession, I would still need to consider the relation of that to possible forms of gentrification.

Perhaps I misunderstand the technicalities of the terms. But it is on the one hand often a rebranding and intensification of the gentrification already at work somewhere, as well as not totally predictable as to its effects. Some go with it and profit from it—but maybe now I am thinking of the experience of being in China. Mai Dian (a friend from Wuhan) has been involved in projects about development around East Lake, notably the privatization of once publicly accessible lands, including “Our East Lake.” For his contribution to the recently-released Wear journal 3, published by HomeShop, he discussed one of the problems in the activists’ resistance to the developments: that many of the farmers and other landowners who they would have hoped to share some solidarity with, had been more disarmed by the imagoes of “contemporary living” presented by the developments and ideas of progress than gathering together a concerted resistance.

Because of its action of government-aided corporate appropriation of large tracts of land, maybe it is not realistic to call this gentrification; my only curiosity is in this imaginary relation to development and contemporaneity. Maybe it would be absurd to humor the idea of a kind of “self-gentrification” though. This imaginary to aim for is brilliantly embodied in the fetishization and commodification of culture—with contemporary art sitting near the top. In many places, including China, art is braided within this tension; it is hard as an artist not to fall on the conspirators’ side at least sometimes.

Richard Florida’s insistence that the economic category of cities could be assessed and enhanced by the number of “creatives” (and homosexuals) is not totally inapplicable if you look at urban change in Beijing, which is not to say that his theories are correct (look at Martha Rosler’s text for an overview of the problems relating art to real estate).

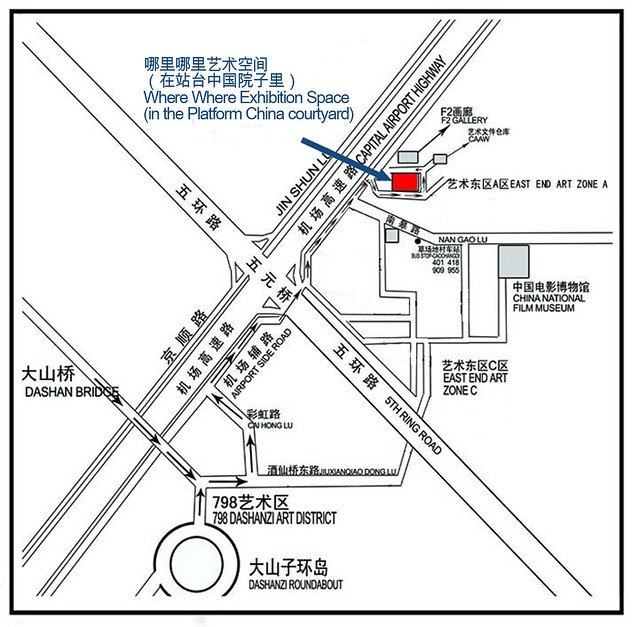

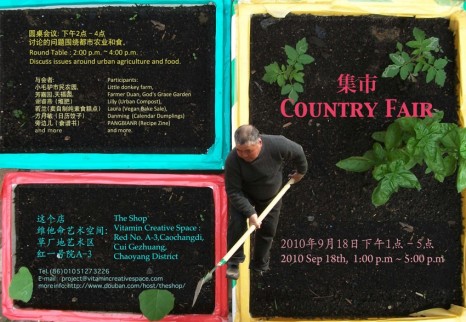

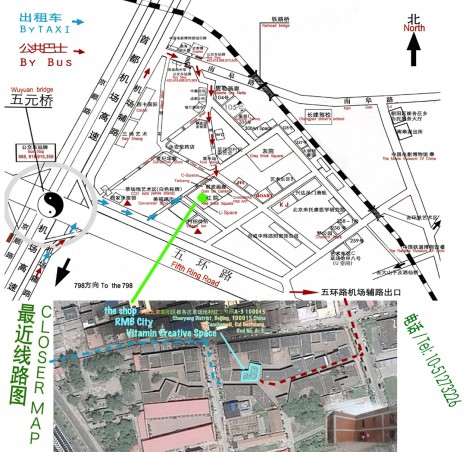

To take a tasteless example, the 798 art district taking over the factory spaces near Jiuxianqiao Road was “authentically” started by artists, and only much later became an art district by edict. Art-inspired rebranding of a place with actual roots in artists first settling there is also taking place in Tongzhou, Caochangdi (which has so far miraculously managed to avoid being razed for at least 2 years since I heard the threat) and other far-out places. In these places, complex cooperation and co-existence between migrant workers, landlord and the art world takes place, though it surely totally disfigures their original states. I guess you could say these also launched a thousand top-down developed gated communities themed on art as well.

In our experience at HomeShop, it is a slightly different story inside the 2nd Ring Road. To some degree, there are the local administrative plans—and in some areas, like Dashilan, I should also mention there are at least nominal attempts to retain local character and occupants at least for the foreseeable future as an architecture firm (sorry can’t recall name at present) develops the area—but the aspect of cultural tourism predates that. (For instance, Nanluoguxiang, which is now the pinnacle of hutong tourism, may have been initiated by some locals, though at present I can’t substantiate this beyond hearsay and less than rigorous journalism.) You also see local hutong-dwellers making adjustments to benefit from the potential returns of tradition (Elaine mentions this in one of her posts on the HomeShop blog, though the residents she mentions aren’t well-to-do by most measures).

HomeShop also adds to the ingredients of the area, of course—I am not sure whether I mentioned an architect friend took over the space across the hutong that used to be an old Shouyi shop? I feel that is a pretty textbook gentrification move, assisted by our presence there to some degree, even if things like this only happen in pockets—but that’s how it happens, if I understand correctly.

So I agree that it is different in China, for instance these several levels co-existing sometimes precisely because they are so different (in the cases of migrant workers living next to fancy condo complexes… at least temporarily), and because of government involvement awkwardly fitting, but I do not think it is a normatively inappropriate to use the term in selected circumstances, especially those relating to culture.

“Artlife,” an upscale mixed use residential development under construction on a stretch of highway near Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province.

Julie: I’ll pick up with the idea you suggest at the end, of a selective application of gentrification to culture. The example of the architect displacing the Shouyi shop could certainly be a part of gentrification, but is it culturally-led gentrification? Or is it more simply economic? Gentrification and culture are connected in a multitude of ways, but I think most commonly, culture is seen as a driver of gentrification. And it’s this conceptualization of culturally-led or culturally-driven gentrification (in its pioneering activity) that most directly, most explicitly implicates artists and creative industry workers. It is rare, let’s say, for an artist or graphic designer or architect to push out a low-income shop in London. More common would be for them to inhabit available spaces in unkempt neighborhoods, rendering them attractive for the middle classes, the urban gentry, who in turn do the heavy-lifting in terms of displacement. This is at least the “common” example, but perhaps this is how Beijing differentiates itself – artists/creatives can directly displace lower income people. Whether the Shouyi shop pushed out or they moved due to the cost of rent, I’m assuming from the example that the architect was able to pay more rent than the Shouyi shop, implying the rising cost of the area, and ensuing displacement. What I find dangerous is simply attaching “gentrifier” to anyone who lives in/moves to a city and works in a creative field.

The Hutong neighborhood changes definitely deserve more attention. But I wonder if the changes in areas like Nanluoguxiang and Wudaoying (which you described as Hutong tourism) should really be understood in terms of gentrification. Why don’t we interpret it in terms of commercialization? I also don’t think enough attention is brought to the longer view – the issue of preservation in the context Hutong evisceration. In German there is the term “Aufwertung” which means “revaluation, giving something additional value,” and I wonder if those changes can’t also be interpreted in terms of simply urban regeneration. This is what I mean by the “gentrification hermeneutic” – that it is a way that people interpret changes, because that is how urban change happens in the cities we are most familiar with. (I mean, it’s its own canon of urban theory!) Of course, the commercialization comes at a cost to the neighborhood, to what it looks like, to what people do there, to the transformation of a residential area into a leisure destination. But, like the case above, I don’t want to label all architects moving in as gentrifiers, and I don’t want to label any street with a cafe as a gentrified area, unless they are really participating in an active process of displacing low-income residents with a higher income group of residents. But, like Elaine said, it’s often the residents themselves participating in these new commercial ventures, so I wonder about actual displacement…

In relation to the attempt to preserve “local character” I want to put in question the idea of an “authentic” art area. From the interviews I did last year, there is broad consensus about the development of 798—from its initiation to its Disney-fication through to the current state. The grassroots nature of its initiation is legendary, especially in the broader scheme of centralized urban planning in China, and served as the inspiration for starting my dissertation. Beyond the consensus about the history, however, the views of artists and curators I interviewed about the nature of artistic space are widely divergent, often contradictory. What is authentically creative seems to at times contradict the very nature of having a stable, long-term, protected, sustainable space. By that I mean, many artists seem to fear stagnation, and I wonder if the very idea of an “authentic” art area is not temporal? Maybe an art space can only be authentic for a moment? Is it maybe in the nature of artistic practice to also be pioneering in terms of occupying or selecting new space (BEYOND the cheap rent argument)?

Michael: Indeed, I use the word “authentic” with great reluctance, and only in the face of the top-down approach, whether that is government or Florida-inspired regeneration. I agree with your assessment of the term otherwise, and how artists are not really looking for it, or expressing or embodying it.

I also realized I had skipped over the point of commercial vs. residential change, which I think is harder to say. Unless we very narrowly define them, figuring out the precise dynamic of the distinction between commercialization and gentrification in that sense would be quite difficult though! It suggests misuse of the terms by many commentators.

Oh, and though this would not represent a very general trend, the issue of how foreigners interact in local economies is something else, both influential (defining standards, prices) and powerless (subject to higher prices at times) at the same time. Really quite marginal though, unless on symbolic level.

Okay, that’s just a quick reply, gotta run! Cappuccinos 加油!

The neighboring Shouyi shop, photographed July 13th, 2012.

时间 posted on: 14 October 2013 |

时间 posted on: 14 October 2013 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: