Several months ago a friend working for the “Un-Named Design” section of the 2011 Gwangju Design Biennale (titled “Design is not Design is Design”) put me in touch with some of her colleagues researching paraphernalia associated with death rituals, presumably as examples of un-named design. My friend was aware of the paper objects I have been making in dialogue with the neighborhood Shouyi, so the researchers asked where they could find these shops. I sent them some images of my objects and research, as I hadn’t even taken images of the insides of the Shouyi stores. But I deliberately refrained from telling them where our neighbors’ store is (it’s directly across from us in the alleyway).

In the summer one of our turtles stopped moving. We buried its body under the shrub by the gates. 夏天的时候,我们养的四只乌龟中有一只死了,我们将它埋在门口的灌木丛里。

This sounds silly now, but in my defense, I swear it wasn’t because I wanted to be the only cultural poacher in the neighborhood. I was simply trying to remain as true as possible to the subject I am following, which from the outset of my acquaintance seemed shrouded in secrecy. When we were preparing the first Beiertiao Leaks a year ago, Xiao and I went over to ask if the Shandong-bred mother-son business team living and working there would place an advertisement free-of-charge in our small newspaper. They refused on the grounds that it was bad luck to publicize as a profession dealing in “superstition.” They didn’t want publicity and wouldn’t allow any pictures or direct mentions of their store printed. Being a sector based on spirituality and superstition, it is kept a close eye on by authorities, and we were told that the government has a monopoly on the funerary industry. Apparently, if one were to buy an urn from our neighbors, it couldn’t be buried in an official cemetery, as they aren’t officially sanctioned. We suspected part of the issue was the instability of their own personal situation. They cagily but politely answered our inquiries, though, so we prepared a short article introducing the phenomenon only to the English-speaking readership.

The title of this brief piece had the Chinese characters “寿衣“ in it though, so the day after distributing the scrappy new copies of the first edition of Beiertiao Leaks we received reprimands from some of the neighbors for even broaching the subject. It seemed from their reactions that, aside from this little shop’s ambiguous relation to the state, as an area of human activity addressing the mysteries of what happens after you die, one shouldn’t speak openly about these rituals.

We had never given it a name, so in order to wish it well, we decided on one: �龟龟 (Gui Gui). 我们的乌龟生前没有名字,但为了祝福它,我们决定叫它龟龟。

Watching a presentation in November by Brendan McGetrick, one of the curators of “Un-Named Design,” we saw an inspiring methodology in organizing a wide range of ideas and artifacts. Toward this, there was a thoughtful attempt to broaden the definition of design to examples of rustic and simple but effective uses of everyday items, scientific innovations and even protocols of action and social situations: “a political protest manual, DNA barcodes, execution procedures, a transcontinental monetary system.” So what made these diverse examples design? McGetrick wrote: “The goal of this theme is to reframe design as a set of strategic solutions to human needs, rather than an ego-driven pursuit of subjective beauty.”

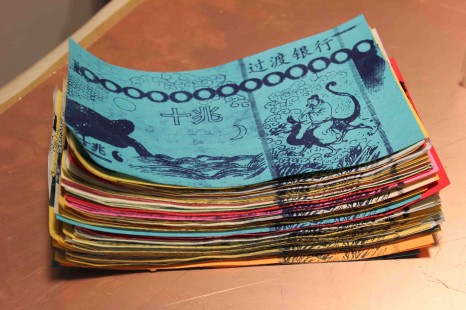

Shouyi goods draw from the design world in the most flagrant sense that McGetrick was reacting against, as they itemize the essential commodities of our lives, and more often consist of the most luxurious fetishes that our cultures share, like money, cars, fancy clothes, mobile phones, and mansions. Their production process rarely results in direct copies, of course. Neither are they really intended to function like shanzhai products, which are in a sense copies better than the original, though they often include subtle and sometimes humorous twists and references to their repurposing. A simple question of materiality determines the boxy appearance of Shouyi goods: they are made of paper and intended to be burnt. The indifference of fire determines a certain indifference of production where other definitions of design come in. The material must adequately combust, thereby expeditiously crossing from the world of the living to that of the dead—but almost anything burns. Having understood this in a peculiarly modern sense, as compared with the more elaborate offerings and sacrifices of bygone times, many people normally opt for rather indifferent forms of tribute to their deceased loved ones or ancestors. The modern sense of sacrifice is that with its democratization has come its effective desacralization and rationalization. However, the ritual of burning Shouyi goods is obviously intended more directly as sacrifice than its substitution with literature (Georges Bataille) or its resonance in all modern music forms (Jacques Attali). It fulfills its function but it must be cheap. Therefore, like all aspects of the modern world, it is conventionally mass-produced and readymade. An average full household set of the nine necessary amenities costs only 15 yuan. If money is no object, one can order the larger dollhouse-size villas or 3/4-scale plasma screens, from a catalogue of hundreds of choices, as the small shops in Beijing usually have them delivered from Hebei manufacturers on request. But logically, as money is an object, the most popular sales are bundles of extremely inflated denominations of “Hell Money,” a very good value-for-your-dollar deal.

What can a turtle do with a car, they questioned. 他们在琢磨,一直乌龟要辆车做什么呢.

But why, I wondered, should this be logical? If Shouyi is about venerating the dead and trying to make their afterlives more dignified, then why are we satisfied with the most cheaply-produced replicas? Is it that the most generic commodities are the most ready stand-in for “pure exchange”? And yet if there is the allowance of kitsch (for instance, pagers and mobile phones that boast of dual-band SIM cards functioning both on Earth and in Heaven, or Renminbi with the face of a god in place of Mao Zedong) then why do we have to buy these sham-brand-name goods from dealers instead of making our own or customizing them to suit our personalities, affections and values? Does it say something about our relationships with our relatives?

With this line of questioning in mind, I produced some very basic paper objects and brought them over to the shop to see if they would accept them to sell. Turning them over, our neighbors commented on the design but confessed they wouldn’t be able to sell them. They were free to set the price and to keep the money, I assured them, while the mother asked dubiously again and again whether they needed to pay me. My only request was to report to us how people perceived them. On our insistence, they said they were willing to take a couple of them, though, just to see what would happen. In my mind, I thought perhaps that at least the sign of the object being made by hand might make a difference to someone. The shop owners said that in the unlikely event someone bought one of them, no matter the price, they were more likely to put them on their shelves and hold onto them rather than set fire to them. This was interesting but still a frustrating compromise; it neatly avoided the problematic desire for real engagement that is the intention of my work, and which determined the relative secrecy and modest scale of my project. In any case, the possibility was there: passing the doors for the next couple of weeks, I was pleased to see my colorful car on the glass counter. After some time it disappeared, though I know it was never sold. They had simply tolerated my meddling enough and couldn’t justify the use of space. We were awkward enough to never again address the topic.

A boy was asked by his mother where Gui Gui is now, and he pointed up toward the dark sky. 一个小男孩问他妈妈,龟龟去了哪里,于是他的妈妈指向夜空.

Rituals surrounding death are a commonality among almost all peoples of the world, though the manner in which I grew up included fairly few practices comparable to Shouyi. For many, death is where religion is concentrated or re-emerges, as it is one of the only unaccounted-for parts of humans’ experience, otherwise always supposed to be understood. I remember funerals of my relatives seeming rather like any other momentous occasion, though blacker in mood. Some believe in heaven, but I don’t. In this, I may differ from other members even of my own family or those close to me (though on my mother’s side, which is Jewish and so the more distinct cultural identity, you could say there is a thoroughly secular tendency among sections of my relatives: in my uncle Alex’s words in an email, “An asteroid will hit the earth and it will all eventually end. It’s all bullshit.”). Traditions, if they can be said, fragilely, to exist in our case, do so only insofar as they punctuate our disparate lives.

In a way, this is the design of culture if not religion, hard-wired or useful enough to withstand all the dissolutions of the modern world. The gestures of a priest, the words of a rabbi or the rites of a woman burning paper money on the street are in some ways designs of community. In the latter case, perhaps it is the design that recreates in symbolic form a familial system of interdependency and debt that structures the lives of the living in China, and acknowledges its extending beyond. The custom of burning paper replicas might be seen to re-establish connections that can never be referred to exclusively as material, even as the designs of the objects themselves are periodically updated or added to.

As I am speaking from a rather uninformed perspective, it is hard to go much further into what might be anthropological, sociological or religious theories of action and belief, and it is also here where theories and beliefs splinter into seemingly contradictory positions. How can we really commune with ghosts if we sympathize with their presence in so utilitarian a manner? This question raised, am I already too late? A whole slew of understandings and misunderstandings of what is real belief underpins its approach as art, pulling in the contradictory directions of doubt and identification. After all, how can we say for sure that this intimacy desired is something actually shared with the people who burn the paper objects for their loved ones? Has the ritual itself not become something “diluted” into expected tradition? And therefore, what is the relation of individuals to their customs; as the outsider, isn’t it simply not my place to enter?

There are in fact many Shouyi shops in our neighborhood. I decided that it was time to approach one of the more “official” shops near the hospital. Like our neighbors they are open all hours, to match the contingency of schedule that moderates the ending of a life. One evening I went over with Chenchen and found that they were much more forthcoming in discussing the topic, rather than more closed as I had assumed. The woman there didn’t think there was actually a difference in the level of legitimacy of Shouyi shops, and she dismissed the idea that urns of so-called unofficial origin wouldn’t be acceptable in official graveyards. The explanation that she instead provided for the difference between the shops was that her family, made up of Beijing natives, did not come from away and had been in the business a long time, so they could be more sensitive in their counsel to local customers. The woman gave me criticisms of the objects I brought her. I returned a week later with a new version of a paper car, this time with hand-painted details, and she asked me where the other items were, the refrigerator, washing machine, wardrobe, bed, and so on. Her attitude was what finally lead me to this betrayal, to loosen my hold on the discretion I felt necessary for real engagement. Activity that operates on rather personal levels sits awkwardly when shifted to a discussion that could be called public, as I am doing now, namely for the reason that doubts arise about the genuineness of the engagement. (Are you a real believer?) This can’t be proven either way, in the end, and the future of this engagement cannot be predicted. Classifying a practice as design is a sign of the removal of belief, as one sees the ends an object is put to, its actualization “as a set of strategic solutions to human needs,” rather than as truth itself (a suspicion that recalls Vilém Flusser’s assertion: “A designer is a cunning plotter laying his traps.”) But if opening up the discussion allows us to see another perspective and to extend the idea beyond fitting in, exploiting or imposing, then that may be when this external custom is made into our own ritual. Rather than reining in spirits for instrumental ends or liquidating everything into the irony that glazes the oblivion lying behind our modern world, artwork can make moves toward becoming authentic—it cannot arrive there too hastily.

时间 posted on: 1 December 2013 |

时间 posted on: 1 December 2013 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: