Can you identify which pictures are from Dalian and which are from Beiertiao?

你能分辨哪些来自大连,哪些来自北二条吗?

Can you identify which pictures are from Dalian and which are from Beiertiao?

你能分辨哪些来自大连,哪些来自北二条吗?

时间 posted on: 9 January 2012 |

时间 posted on: 9 January 2012 |  发布者 author: michael eddy |

发布者 author: michael eddy |  comments (3) |

comments (3) |

Visibility/publicity……….可见性/公共性

Michael EDDY (问题/questions) & 麦颠 MAI Dian (回复/responses)………[节选/excerpt

Does the way in which we live have to be visualized? Of course not; but it seems that visibility is an important part of both art and activism.

How do both art and activism approach a public?

我们生活的方式必须被显现出来吗?当然不是;但是可见性似乎对艺术和行动主义都很重要?

艺术和行动主义如何走近公众?

我相信,传递欲求很普遍地发生在几乎每个人身上。行动主义,即便是最个人主义、无政府主义,更愿意实现一种与他人心灵感应的人也期望得到同情。这从无政府主义的自我独立表达的小册子和独立媒体可以看出来,无论其所能涉及的“公共范围”有多大。而对于其他政治色谱的大多数运动者而言,社会动员是重要手段,动员公众的支持与参与非常重要,相应的,媒体对其而言总是重要,尤其来自大众媒体的报道。假如我们将“上访”看作是一种具有中国特色的行动主义,我们就可以看到,这样的行动多么依赖于媒体,以至于将记者或知名人士/意见人士看作是人士的救命稻草,希望它们的报道与发言能够形成一种社会压力,因为,对于他们而言,这是一种可以将自己的“冤情”传达到清廉的上层的特殊途径。

同时,我想,绝对“自言自语”的艺术几乎是不存在的。一个艺术家在工作室里进行文本图像声音创作时可以在某种程度上看作是“自言自语”,但一旦作品出了工作室,那它就不得不面对公众—不管其所面对的公众数量与范围有多大。这个时候,作品甚至都“不再属于艺术家本人”了。宫廷艺术家为皇帝服务,宗教艺术家为上帝服务,那么现在呢?中国的艺术家大部分为市场服务,或者为一个值得怀疑的所谓集体名词“消费者”服务。最新的一期《新周刊》的封面主题便是艺术的“兑现主义”。这个过程中,艺术不仅不避讳,反而使劲浑身解数,要俘获“大众”:物的艺术化,艺术的物化,去政治化,“创意”产业化。

即便是一种所谓的激进的政治艺术,大家也没有想过避免大众,相反,他们也在以自己的方式解释“为人民服务”, 比如戈达尔。东湖艺术计划的被发起的目的,是因为寻求在主流媒体与本地媒体被审查的新闻与事实,能够藉由另一种语言与信息通道—艺术的语言—从审查里挣脱出来。这个信息会发散到什么程度,不会有人保证,因为艺术毕竟在某种程度上“特殊的语言”。计划的发起人之一李巨川是戈达尔的爱好者,另外一个发起人李郁也是戈达尔的爱好者。李郁自己的摄影作品,是通过对新闻再现(news representation )的再现(representation of the news representation) 来试图反诘主流的媒体话语。他将类似的手法应用了东湖艺术作品中。对地图再现的再现(representation of map representation),不仅历史和媒体说谎,地图—-在某种程度上拥有科学的威严—同样也在说谎。那么,这种通过画面(照片+装置)展现出来的的艺术语言,会在哪些媒介上,被哪些人所接受?事实是,艺术媒体或者研讨会,讨论会。而接收者大多数是接受过专业艺术训练或者有所阅读的业余爱好者。艺术所能影响到的,可能只是一个“公众”集合中的少数人(甚至这些人具有某种专业主义倾向),更加无奈的现实是,艺术所关注的事件的直接“当事人”,比如,失地的农民,明确地告诉我们“看不懂”。

当然,看不懂的,不仅仅是艺术,即便是“我的东湖”网站上的文章(试图从各个方面去论证开发的不合理性,并揭露开放过程的野蛮性,暴力性,反民主性等等),农民也表示看不懂。所以,艺术和行动主义在如何接近“公众”的问题,面临着许多我们所谓的沟通的障碍。这沟通的障碍,不仅仅是“语言”与“言语”的问题,也与价值观、直接性、以及大家对一个“复合”问题的关注点的差异相关。对于农民而言,他们需要直接的语言,也依赖于一种最简洁的逻辑:“地被夺了,需要赔偿,赔偿需合理”(且“和平”)。

而艺术和行动主义的焦点,大多数则在“规划民主”,“环境保护”。这里存在一个巨大的断裂带:多数农民并不愿意继续耕种,保存其土地,只是希望赔偿更合理。而环保,则希望保存耕地/渔场与湿地,农民的补偿问题被弃置一边。关于“公共空间”的争论,焦点集中于“民主”,并不是“公共空间”是一个什么样的空间:公园与湿地,哪一个更“公共”?因此,艺术在这里的问题是,究竟它是进入了一个所谓的“事实”,或只是将一个“事实”作为一个政治观点的现实证据?

等等。

行动主义和艺术在某种程度上都是对媒体开放的。这是往往其通向公众的一条重要途径。当然,这里面有很多的问题会在现实中分裂出来。

Do we need to produce things—models, discourses, trains of thought, if not outright objects—because of this program of visibility?

我们需要因为可见性的要求而制造些什么东西吗?即便不是有形的东西---如榜样,研讨会,思想训练等?

是否需要? 回想起过去的一些经验,我的问题可能不在于是否“需要”, 而是“如何”传递以及传递“什么”信息—-既然传递欲望是不可避免的,且现实中,我们也未曾“一概”避免。而且,这只是我们一厢情愿,从我们的角度来看这个问题。另一厢,Visibility/publicity本身也包括了其他的面向:visibility,除了所谓的亲密关系的范围,以及个人以DIY伦理自我表达,若是要面对所谓的大众媒体(无论是官方媒体还是商业媒体。中国并没有真正意义上的“公共媒体”—所以不便加以评论),那么它的“可见性/公共性”的生产机制是什么? 大众媒体出于什么动机要报道和传递“this program”? (某)艺术又如何籍此扩展其范围?其意义是如何发生外溢的?这个过程当中是一个“有选择的过程”,其结果是选择后有特定导向的结果吗?它是抱着“启蒙”的目的?或满足一种“满足与快感”的需求,还是其中包含着两者兼有的一种所谓的曲折的策略?也许,这需要细致且谨慎地考察媒体的话语生产。

那这所谓的visibility又是怎样出来的?是因为distinguishability?比如,我们这里所关注的“食物”,就其生产方面而言,它是否提供了一种对当前食物生产模式与安全危机的替代方式,甚至是现阶段一个可靠的an alternative to instead of capitalism for the future? 或者,它只是中产阶级的休闲方式,其意义和“农家餐馆”甚至“高尔夫球场”,旅游胜地并没有根本区别,它是新的fashion(就像记者总是以为的“时尚达人”,或者,通过“时尚达人”才能报道—-政治是要避免的)?

那么,这个program是怎么样被看的(how is it seen by the others, including media?) 如果你拒绝开放你的园子,另当别论。但如果你开放,那么你的生活(或者说实验)会如何被他人所解读,所阐释?你的实验可能的结果,常常被他人输入另一套(或者多套)话语模式,是不是?怎么来处理这样一种局面—当误读(misrepresentation, 且不说ignorance)?当然,这里需要往前追溯一下,即,在出发点,你打算想将你的生活方式当作一个开放的艺术品,放弃意义的所有权,对所有人开放?还是打算我应该说出我自己所想的(因为你已经在做你自己想做的)?完全的开放,可能会有危险,即所谓的“收编”。比如,被一家以lifestyle为主的媒体将你并置在咖啡馆、购物广场、美食以及美甲店或者创业成功案例的页面之间时,你的感觉是怎样的?

按照结构主义的逻辑,如果你自己不说话,那么,社会结构就会替你说话。

++++++

Does the way in which we live have to be visualized? Of course not; but it seems that visibility is an important part of both art and activism.

How do both art and activism approach a public?

I believe the desire to transmit occurs in everyone. As regards activism, even the most individualistic anarchist or the individual preferring spiritual connection long for sympathy from others. This is reflected in self-expressive anarchist brochures and independent media, regardless how large its public sphere extends. Yet for other social movement actors, social propaganda is a crucial tool, as the participation and support of the public is important, correspondence with media likewise, and especially reports from the mass media.

Viewing petitioning as a form of “activism with Chinese characteristics,” we see how much these actions rely on media. To the degree that reporters and opinion-makers become the saving straw for petitioners, hoping reporting and giving-voice can form and inform social pressure. For them this is an exceptional way of transmitting their “grievances” to the uncorrupted political upper classes.

Meanwhile an art characterized by absolute auto-discourse doesn’t exist. An artist working with text, images, sound in own his or her studio can be viewed as one involved in an auto-discourse. But once the work leaves the studio then it must face the public, again, regardless of the number or extent reached, which is out of control. The work no longer belongs just to the artist. Court artists served the emperor, religious artists serve god, and the majority of Chinese artists now serve the market, or some dubious “consumer,” an abstract collective. The newest edition of News Weekly consequently featured art’s “contractual fulfillment” on its cover. In this process, not only does art shun the taboo of the mass, on the contrary, it tries with all its might to enslave the mass: the artification of the object and the objectification of art. De-politicization and innovative industrializing.

Even in so-called radical political art, artists don’t think about avoiding the public/mass. On contrary, they are defining “serving the people” in their own ways, for example Godard. The purpose of East Lake Project was focused on the liberation of censored contents through a different language and information channel, namely the language of art. The extent to which this information will circulate, no one will know, because art to a certain degree is a special discourse. One of the East Lake Project initiators, LI Ju Quan is a Godard fan, as is the co-initiator LI Yu, whose own photo work involves the subversion of mainstream media discourses through “representation of the news representation.” Employing similar means for East Lake Project, concerning “representation of the map representation,” showing not only history and media are lying, but also the map, which assumes the authority of science. Therefore, this art language manifests through image: what kind of media/people will find this language acceptable? In this case, photo + installation. The fact is those who accept these are art media, symposiums, seminars, workshops, in other words circulating within its own sphere. The majority of recipients received professional art training or make up amateur art readerships. Interested population more likely limited to a minority of the public. These people might have an inclination to professionalism. More disheartening are the responses of the protagonists of those events that this kind of art concentrates on, for instance the farmers who lost their land, who unambiguously and emphatically tell us they don’t understand.

Of course art isn’t the only incomprehensible thing. The articles on “My Donghu” website [wmddh.net; currently inactive] are just as incomprehensible: trying to demonstrate irrationality of the project from different angles, to reveal barbarism, violence, antidemocratic tendencies within the area’s development. So the question how art + activism approach the public while facing a so-called communication barrier is not only a matter of discourse and language but also of the value standards, immediacy and difference intrinsic to people’s opinions concerning a compact issue. The farmers, they need direct language, and the simplest logic: land is taken away, compensation is needed, such compensation should be just (also in a peaceful manner).

Yet the focus of art and activism in the main is concerned with regulative democracy/environmental protection (ie. the bigger issues), and here exists a big gap with the farmers. Most of the latter do not want to keep farming, and preserving the land is only a means or way to bargain for more compensation. Those who commit to environmental protection want to preserve arable land/ fisheries/wetlands and therefore the problem of compensation is suspended. The debate concerning “public space” is focused on democracy, not on the question of what kind of space is the public: parks and wetlands, which one is more public? Therefore the problems for art to investigate are whether art itself has become a “fact” or whether it is just using a fact as evidence for a political view. Activism and art are to a certain degree open to the media; this is a crucial path to reach the public. Of course, many singular problems will multiply into a plethora in reality.

Do we need to produce things—models, discourses, trains of thought, if not outright objects—because of this program of visibility?

Do we need it? Let’s recollect past experiences. Our problem may not lie in whether such undertakings are needed, rather the how of transmission and its what. Since the desire of transmission is inevitable, in reality we have not altogether avoided it. Furthermore, this is just our wishful thinking. On the other hand, visibility, publicity themselves have other facets. Visibility—other than its so-called sphere of intimate relations and the self-expression through DIY—if they are to face so-called mass media, what would their production organism be? What would their visibility/publicity production mechanism be? (note: If they are to face so-called mass media, be it official or commercial, China does not have “public media” in a true sense, so we can’t comment much about that.) Out of what motive would mass media report and transmit “this program”? How can a certain art extend its sphere of influence through this, how can its significance exceed its boundaries? Of course, there is a process one could choose, yet the result is the outcome of specific channeling (manipulation). Does it possess a goal of enlightenment or satisfy a demand of fulfillment and pleasure, or maybe it is a roundabout strategy that incorporates both. Perhaps this demands a meticulous and conscious investigation of how media produces discourse. How does this visibility come about, is it because of distinguishability? For example, the food we are concerned with here, in terms of its production, has it produced an alternative for the prevalent mode of production and its consequent safety crisis? Or is it just a reliable alternative, or a form of recreation for the bourgeoisie—then its significance at bottom is not so different from “farmers’ restaurants,” and even golf courses, and other tourist sites. It is the new fashion (which has little to do with politics).

How is it seen by others, including the media, if you refuse to open up your garden, is a different issue, but if you do, your life or experiment will be interpreted/defined by others. The result of the experiment will often be imported into another mode of discourse, no? How do you solve this state of misrepresentation let alone ignorance? Of course, we must backtrack a little, to the the point of departure, which is the question: do you want your lifestyle to be an open work of art? Thus relinquishing your authority over its meaning, or do you want to do just as you think (because you are already doing what you want to do). Absolute openness can be dangerous, danger lies in being subsumed/coopted. For example, when media who features lifestyle puts you side-by-side with coffee shops, shopping malls, cuisine and nail salons, and other cases of entrepreneurial undertakings, how does that make you feel?

According to structuralist logic, if you do not speak, then the social structure will speak for you.

时间 posted on: 6 September 2011 |

时间 posted on: 6 September 2011 |  发布者 author: michael eddy |

发布者 author: michael eddy |  comment (1) |

comment (1) |

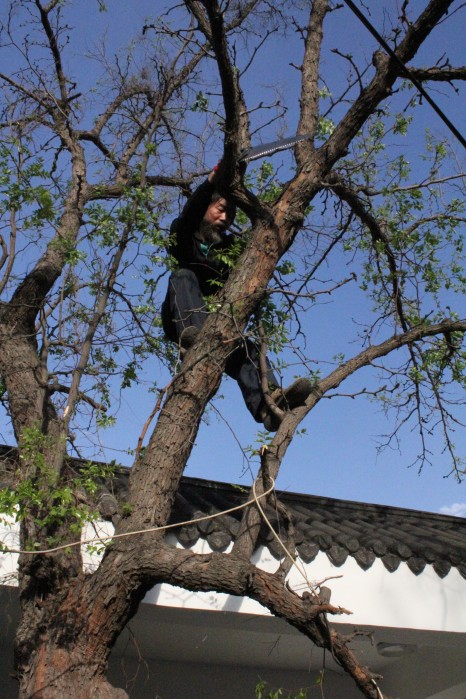

photo by GAO Ling

photo by GAO LingAfter trying to begin to write for quite a long time now, it finally comes down to seeing no other simple way to begin but with all the complexity of ‘I’, which means that proper reading and research are lacking enough to make one unable to (attempt) to pursue a more objective line of reasoning and/or explanation. In all honesty, the last months have dried up words, and parched like this city, thoughts do not find language in balanced cycle. Even the pronouns don’t dance as much as they used to, as per those (known for) past avoidances of the reflexive pronoun, and I wonder which particular subjectivities have been lost along the way.

I think about the past often, but I’m not so nostalgic.

Where does this ‘I’ come from, this ‘I’ that has somehow come in the last years, across particular oceans and with the looking back upon those far fallen bridges? There is a loathsome identity game going on here, and recent events have triggered repeated keywords, or perhaps it’s simply grammar.

‘I’ cannot separate from this question of what ‘this’ is, but where we were led astray during the conversation was the point at which things needed to be named, where it matters how we define [定义] a certain audience, forms of art-making, goals and Five-Year Plans. The fact is that I don’t want things to fit so easily into well-written descriptions, institutions or fixed modes of communication.

Communication, or art, for that matter, does not occur in ‘I’ alone, or even by mere grammar. The signifieds are too complex these days, like Hollywood hoaxes piled upon political ones. The politics exist in representation as much as in our language, and ‘I’ should get confused with ‘we’ or ‘she’ or ‘he’ much more often than it does, perhaps.

Name Game

如果唯一可以信任的是个体对自我的主体性的信任的话,那么被分裂的不是自己,而是系统,也正是系统的分裂促成了一种生成(becoming)。

If the only thing to be trusted is individuality’s subjectivity, then being divided (split-off) is not the self but the system; it is a form of becoming precipitated by a fissure in the system. [1]– 麦巅 MAI Dian

Some friends at Womenjia Youth Autonomy Lab [“我们家”青年自治中心] in Wuhan recently had one of their texts re-translated at China Study Group, and what strikes me most is the need for a rethinking of terms amidst the proliferation of #tags# and “elevator pitches”. In the same moment that some may ask us for more clarity in explaining a practice, or a work, it becomes also useful to note when the omittance of certain signifieds allows a form of agency that cannot be practiced otherwise.

The Womenjia Youth Autonomy Lab describes itself thus on its Douban page with a question mark, and this, as shown in his text, is fraught with all the layers of subjective and objective dilemma that come with giving “the house a name”:

只要出力,物质空间就来得颇为容易,改造也颇为顺手,但超乎预料的是,「自治」招牌甫一挂出,社会关系就立马需要重建,破与立的冲撞此刻就显出其厉害来了。新的关系还未有「蓝图」…

So long as you put forth the effort, physical space will arrive rather easily, and transformation will proceed smoothly. What we didn’t expect was that the moment we hung up the sign with the word “autonomous,” everyday social relations would have to be redefined. From that moment onward, the destructive and constructive sides of change began to collide with each other. New relations have no blueprint. [2]

Words like ‘I’, ‘community’, ‘representation’ and some of their possible outputs—’we’, ‘society’, ‘art’ and ‘media’—exist likewise in constantly shifting relation. This occurs at the level of semantics but also in the means with which we can create those outputs. I think we somehow failed to get to this in all the discussions of ‘alternative practice’ that have gone on lately [3], and this is also why it may be quite tricky to look at such researches (at least contemporarily) as anything more than an index, or a means of self-reflection.

This goes back to the ‘I’, and of course, its evil partner ‘other’. Alternative arts practices and many other forms of cultural production in China are catalysed to a great degree by ‘the foreign others’, and this can be explained largely by matters of economy, varied forms of thinking of agency and initiative, as well as, at a larger scale, ideas about what ‘DIY’ or ‘politics’ mean (and where they coincide). Media finds itself intertangled within all of this, from the rhetoric of finding Chinese origins for Western initiatives [西学中原], to the politics of representation and yes, language. This tends to be frustrating or opaque-rendering for those seeking forms of lateral exchange, and a lot of the time, well, the vocabularies are just too different. This is not to say that nothing can be exchanged, but we should be careful of what ulterior motives drive seemingly open-ended discourse. Desire is rarely so easy as the statement ‘I want you’, and more often than not, “the ‘tragedy’ that is love is simply laughed at”. [4]

I’m circling around here. After cynicism about cultural exchange, more recent topics that have come up as possible focuses for our next publication include translatability, opacity, ballsy. It sounds vague, but I trust that we are already in the same vein. At the same time, we are thinking about how different forms of media we utilise can be better refined to address the who, what, where, why and when we would like to communicate. This is why I am relieved and re-struck to refer to DYAC again, albeit from the somewhat sophomoric attempt of our own Beiertiao Leaks. This very slow day newspaper was a first attempt from our new home base at Beixinqiao to organise a form of media that is participatory, multiplicitous and public. It is not an equal exchange. But, as Michael says, it’s “a conversation starter”.

All of this rambling, likewise, is a kind of conversation starter. For HomeShop and for optimistic efforts to understand the juxtapositions between language, art and politics. “最正经的如「政治」,并不是理所当然的政党与特殊利益集团的国家治理,甚至法西斯极权,它更是我们作为一个有主体性的人参与社会关系的建设…” Politics not as in the “state administration by parties or special interest groups,” but as “our participation as subjects in the construction of social relations”—a kind of grammar, perhaps—involving more than one pronoun. [5]

——–

时间 posted on: 6 February 2011 |

时间 posted on: 6 February 2011 |  发布者 author: e |

发布者 author: e |  comment (1) |

comment (1) |