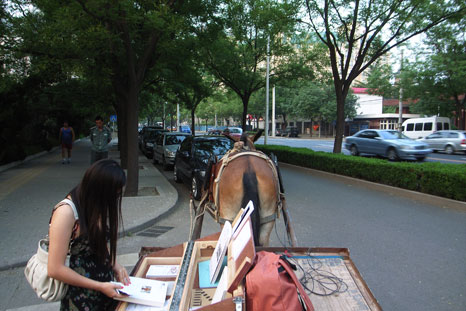

《穿》杂志在驴子当代艺术协会的移动图书馆。Wear journal takes part in the Donkey Institute of Contemporary Art‘s mobile library.

《穿》杂志在驴子当代艺术协会的移动图书馆。Wear journal takes part in the Donkey Institute of Contemporary Art‘s mobile library.

__

Along the lines of the donkey (re: recent outing), who stands the rather lonely figure amidst the chatty crowd, it is a questionable act to gather with a basket of beers from around the world on the occasion of artist books. Or, it’s just that one mustn’t gather here. Security guards erupt upon slyly innocent donkey caretakers, but artists’ non-communication says enough to call the big brothers who have a bit more persuasive powers. The Donkey Institute and its books were not necessarily here to make a stand, though, so a few prods of the ass and everyone is fine to make a leisurely dashed and dotted caravan further up the street, where we do not disturb the south entrance of Lido Park! It’s a smooth-awkward transition, a meandering gathering that slips away just as the 城管 chéngguǎn slide in with their marked car. The sight of an indignant security guard explaining gross offenses to the 城管 chéngguǎn fades away behind us.

Half a block away, the roving Donkey Institute of Contemporary Art settles into its new location at a busy intersection of northeastern Beijing during rush hour. Passersby range from pyjama-clad grandmothers to young boys on electric scooters and white collar foreigners. Donkey’s rough institutionalising feels like the park we’ve just left, and casual social gathering leads quite naturally to sitting on the ground with knees up, idle chatter, dangling cigarettes. There are stark contrasts within the formations of a socius: park up-spring, lonely donkey, noisy traffic.

And friends. I don’t know many of you, but it supposes that our mutual presencing here around the book cart of a lonely donkey brings us together. What Nancy says about the lack of feeling of the social contract, we know must be much more demanding than that. Like the tall friend in the yellow t-shirt with the kind of face one cannot place as young or old; his smile tells of feeling in everything. He is the happy friend of Michael or Yam or Edward, warm to everyone, always smiling. He puts his long arm around the shoulders of the friend to whom he may be talking to at any moment. Happy, friendly visitor, come join us for dinner. And yet further inquiry reveals that the terms of these relations may make themselves felt in another way; he is an observer, sent by the 城管 chéngguǎn.

公安局的工作员非得要我们拍到好看一点! The Public Security Bureau officer insists upon several takes before we get it right.

公安局的工作员非得要我们拍到好看一点! The Public Security Bureau officer insists upon several takes before we get it right.

__

At the end of a long dinner table, Yam blurts out in English, “He’s police! He’s got a badge!” This kind of information can stun and lend unease to any meal, but after a moment of conscious staring――and seeing that our only potential subversion of donkey cart and artist books has already gone home――Xinjiang food at a long dinner table proceeds in just about the same lively manner. Voices and chopsticks criss-cross in dynamic fashion. The friendly observer is not merely a passive onlooker; during the course of the meal he charmingly makes his way around all edges of the table, offering cigarettes, getting to know everyone. These are tactics, yes, but perhaps no more than those of the smitten out on a first date. Let us get to know the 公安局 Public Security Bureau, of which I later find out he is a part. I am uncertain what forms of freedom or rights I may relinquish in seeing a particular light within this encounter, but perhaps that should depend upon how many dinners we share with those that are watching us. The reports must be written anyway.

As the group disperses after dinner, friendly yellow-shirted PSB officer and I happen to be left alone together to walk a short distance in the same direction, and rather than any other proposed confrontation with the authoritative kind, it is, yes, filled with the awkwardness of potential romance. Me and the PSB! We ask questions about one another. He explains to me how our meeting was set up by the chéngguǎn, which wouldn’t have occurred in the past but now work together after a recently created triumvirate between the police force, PSB and the chéngguǎn (usually separate policing bodies with varying jurisdiction). Why? What threat can there be to fear?

Yellow-shirted friend likes Hong Kong pop music, has been thrust into this line of work by his grandfather and father before him, and now patrols the Dashanzi area in plainclothes as a day-to-day, perhaps making friends with all sorts of people. Our date is not so special, I guess. Even so, my inner monologue is conscious of the rising tension as we walk towards our departure point. He insists upon escorting me all the way to my bicycle, and I wonder what the equivalent of a goodnight kiss would be in this situation.

In the end, I ride away, and he waves goodbye, calling out, “路上要小心!” I like him so much. This could be ridiculous, in consideration that what we in other realms may have considered right could have been infringed upon tonight. It is simply that the contracts make themselves felt in a very different way here, and the small heart of our interactions with representatives of the State are like the awkward openings of an encounter beyond power. I don’t know. This was perhaps just an exception, but it seems like a resolved attitude for many of us in the neighbourhood, where it is possible to acknowledge the overbearing authority of the State and yet pay no heed to it. Everything is means. Like faded propaganda posters, I don’t know how my mind has changed already.

时间 posted on: 24 July 2010 |

时间 posted on: 24 July 2010 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: