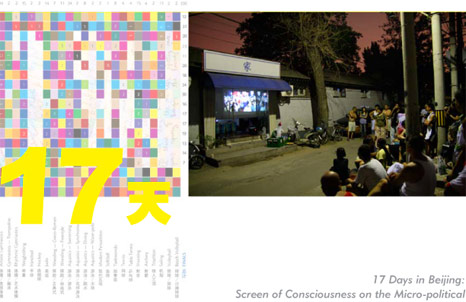

I was thinking about our discussion on Olympics, events at 家作坊 and public space. I don’t know how far we can explore the way the Olympics have actually changed the practices of urban public space during that period…or at least, this is probably not a question that can be answered yet but will request some time and distance before finding an answer.

What we could explore, though, is how far the Olympics, as a public event, have allowed you to produce events at your place that were justified…precisely because of the high publicity of the Olympics. Would these events have been possible otherwise? It is sure that the Olympics have raised many restrictions about the use of public space, yet they have also allowed community restrictions to loosen (and thus made you organize parties in the hutong without major problems). I find this negotiation between restrictions and freedom very interesting…definitely needs some more research!

Here is a piece of an article published by Ash Amin [(2008) ‘Collective culture and urban public space’, City, 12:1, 5 – 24], where the author explores how public space is actually working (or not), which are the dimensions and interactions between humans —- but also between humans and materiality —- that allow encounters in the public space. Can send you the paper if you like.

The ethics of the situation, if we can put it in these terms, are neither uniform nor positive in every setting of thrown-togetherness. The swirl of the crowd can all too frequently generate social pathologies of avoidance, self preservation, intolerance and harm, especially when the space is under-girded by uneven power dynamics and exclusionary practices. My second claim, thus, is that the compulsion of civic virtue in urban public space stems from a particular kind of spatial arrangement, when streets, markets, parks, buses, town halls are marked by non-hierarchical relations, openness to new influence and change, and a surfeit of diversity, so that the dynamic of multiplicity or the promise of plenitude is allowed free reign. There are resonances of situated multiplicity/plenitude that have a significant bearing on the nature of social and civic practice. At least five that merit conceptual and practical attention can be mentioned.

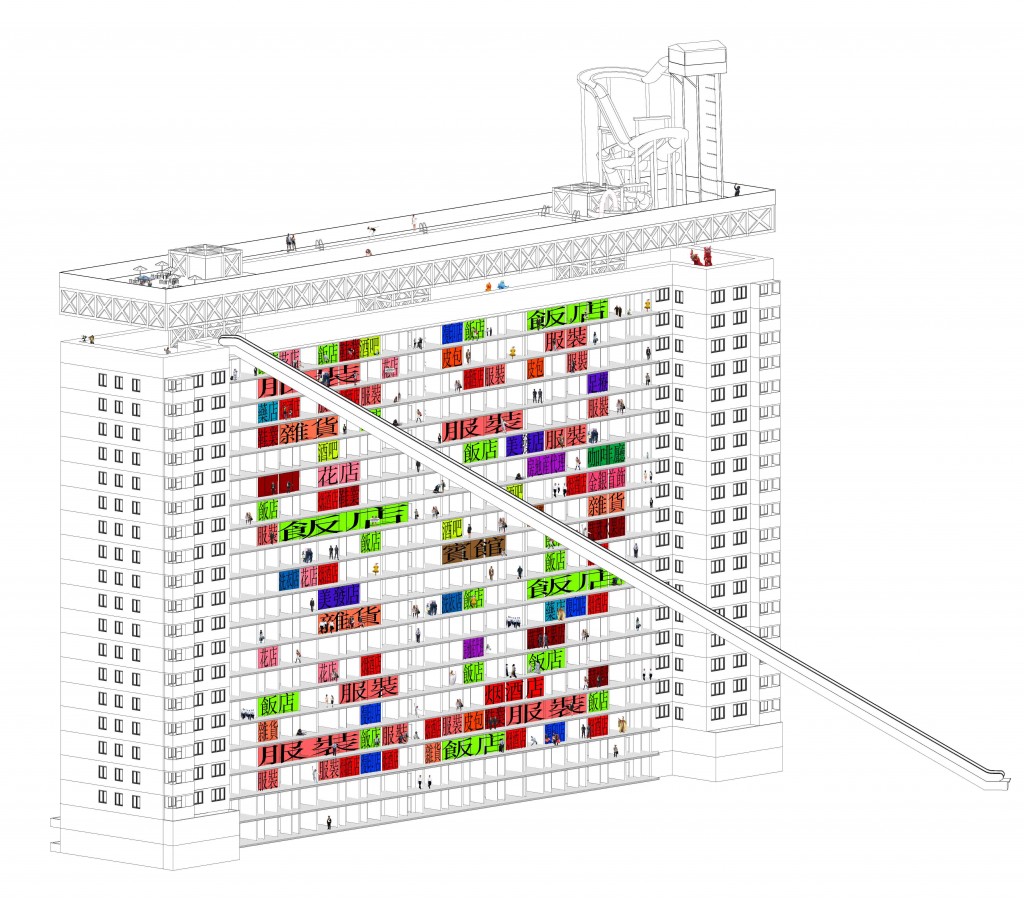

The first resonance is that of surplus itself, experienced by humans as a sense of bewilderment, awe and totality in situations that place individuals and groups in minor relation to the space and other bodies within them. What Simmel tried to explain in terms of behavioural response among strangers when placed together in close proximity in urban space-from bewilderment and avoidance to indifference and inquisitiveness–might be reinterpreted as the shock of situated surplus, experienced as space that presents more than the familiar or the manageable, is in continual flux and always plural, weaves together flesh, stone and other material, and demands social tactics of adjustment and accommodation to the situation (including imaginative ways of negotiating space without disrupting other established modes, as shown in Figure 2). The resonance of situated surplus, formed out of the entanglements of bodies in motion and the environmental conditions and physical architecture of a given space, is collectively experienced as a form of tacit, neurological and sensory knowing (Pile, 2005; Thrift, 2005a), quietly contributing to a civic culture of ease in the face of urban diversity and the surprises of multiplicity.

These surprises are rarely disorienting, for a second resonance of situated multiplicity is territorialization; repetitions of spatial demarcation based on daily patterns of usage and orientation. The movement of humans and non-humans in public spaces is not random but guided by habit, purposeful orientation, and the instructions of objects and signs. The repetition of these rhythms results in the conversion of public space into a patterned ground that proves essential for actors to make sense of the space, their place within it and their way through it. Such patterning is the way in which a public space is domesticated, not only as a social map of the possible and the permissible, but also as an experience of freedom through the neutralization of antipathies of demarcation and division–from gating to surveillance–by naturalizations of repetition. The lines of power and separation somehow disappear in a heavily patterned ground, as the ground springs back as a space of multiple uses, multiple trajectories and multiple publics, simultaneously freeing and circumscribing social experience of the urban commons.

A third and related resonance of situated multiplicity is emplacement. This is not just everything appearing in its right place as a consequence of the routines and demarcations of territorialization. The rhythms of use and passage are also a mode of domesticating time. Public spaces are marked by multiple temporalities, ranging from the slow walk of some and the frenzied passage of others, to variations in opening and closing times, and the different temporalities of modernity, tradition, memory and transformation. Yet, on the whole, and this is what needs explaining, the pressures of temporal variety and change within public spaces do not stack up to overwhelm social action. They are not a source of anxiety, confusion and inaction, and this is largely because of the domestication of time by the routines and structures of public space. The placement of time through materialization (in concrete, clocks, schedules, traffic signals), repetition and rhythmic regularity (so that even the fast and the fleeting come round again), and juxtaposition (so that multiple temporalities are witnessed as normal) is its taming. Accordingly, what might otherwise (and elsewhere) generate social bewilderment becomes an urban capacity to negotiate complexity. The repetitions and regularities of situated multiplicity, however, are never settled. This is because a fourth resonance of thrown-togetherness is emergence. Following complexity theory, it can be argued that the interaction of bodies in public space is simultaneously a process of ordering and disruption. Settled rhythms are constantly broken or radically altered by combinations that generate novelty. While some of this novelty is the result of purposeful action, such as new uses and new rules of public space, emergence properly understood is largely unpredictable in timing, shape and duration, since it is the result of elements combining together in unanticipated ways to yield unexpected novelties (DeLanda, 2006). Public spaces marked by the unfettered circulation of bodies constitute such a field of emergence, constantly producing new rhythms from the many relational possibilities. This is what gives such spaces an edgy and innovative feel, liked by some and feared by others, but still an urban resonance that people come to live with and frequently learn to negotiate. This is what Jacobs (1961) celebrated when championing the dissonance of open space, receptive to the surprises of density and diversity, manifest in the unexpected encounter, the chance discovery, the innovation largely taken into the stride of public life.

A final resonance can be mentioned. We could call it symbolic projection. It is in public space that the currents and moods of public culture are frequently formed and given symbolic expression. The iconography of public space, from the quality of spatial design and architectural expression to the displays of consumption and advertising, along with the routines of usage and public gathering, can be read as a powerful symbolic and sensory code of public culture. It is an active code, both summarizing cultural trends as well as shaping public opinion and expectation, but essentially in the background as a kind of atmospheric influence. This is why so frequently, symbolic projections in public space–lifted out of the many and varied material practices on the ground–have been interpreted as proxies of the urban, sometimes human, condition. There is a long and illustrious history of work, from that of Benjamin and Freud to that of Baudrillard and Jacobs that has sought to summarize modernity from the symbols of urban public space, telling of progress, emancipation, decadence, hedonism, alienation and wonderment (Amin, 2007b). Similarly, politicians, planners and practitioners have long sought to influence public opinion and public behaviour through the displays of public space.

时间 posted on: 27 April 2013 |

时间 posted on: 27 April 2013 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under:

“Pyjamas, nylon stockings, and other Olympic dreams” [photo by Jeroen de Kloet]

“Pyjamas, nylon stockings, and other Olympic dreams” [photo by Jeroen de Kloet]