In light of the last Happy Friends Reading Club meeting’s topical foray into the “aesthetics of sustainability” (addressed in an essay of the same name by Hildegard Kurt, as introduced by Victor Margolin’s text in Beyond Green: Toward a Sustainable Art), the validity of pinpointing or negating the any-be-all-whatever of contemporary art still stands at insecure shoulder to the hierarchies established by the art system, the values garnered by its economics and institutions and indices of fame. M.E. pointed out an important question raised by Margolin, of a possible aesthetics of ethics to describe those ambiguous projects (in his example, Mel Chin’s Revival Field “in which the artist explored the use of plants to remediate the soil in a landfill that had been contaminated by heavy metals.”) which become artistically difficult to interpret.

And while perhaps we should have been examining the ethics of any artistic practice all this time, it’s perhaps also true that a sublime—art historically speaking—needs not adhere to any particular ethic (unless that is an ethic in and of itself), as it induces the viewer (until glorious afterlife or perhaps now merely through the clicks) to a mode not unlike Agamben’s bumblebee, in a captivated kind of productivity, guillotined and still sucking for all it’s worth. This is perhaps the pre-thought to what I mentioned in the last post, “towards a ‘new’ language starkly founded in realism, unimaginative”, where aesthetics are the attributes of wallpaper styles and design tools to address real world issues. Not unimaginative by any means, but I wonder at which point in such an assembly line can meaning be redistributed.

Margolin’s essay calls for “a new aesthetic to embrace the three categories of object, participation, and action without privileging the conventional formal characteristics of objects. In this aesthetic, the distinctions between art, design, and architecture will blur as critics discover new relations between the value of form and the value of use.” If we have come towards forms of art-making that ‘see’ us through these categories, it becomes inevitable that ethics comes to the fore, and the voice of the artist be taken much more seriously than “wildly expressionist”. This puts art and its blurriness in danger of always being held to scales of use value, but let’s hope that it is still possible to expand the realms of possibility via the languages that we use, the way the signs are laid to their signifiers, to understand modes of transmission as the aesthetics of our ethics.

In an upcoming exhibition entitled All that Fits: The Aesthetics of Journalism, curators Alfredo Cramerotti and Simon Sheikh bring art and journalism together as “two sides of a unique activity; the production and distribution of images and information.” This elevation of the importance of forms of transmission alongside the production of the object itself is crucial to contemporary thought. It is a call upon the collective, or maybe a confirmation that past forms of beautiful solitude are less relevant in our ways of production, parallel to the ethical consideration of the other as artistic criterion. The press release of the show goes on to state: “Whereas journalism provides a view on the world, as it ‘really’ is, art often presents a view on the view, as an act of reflection.” These are both response-based attitudes towards creation inseparable from their need for reader/audience reception (one could go into that other discussion on intention here), and in our case, perhaps a fitting media for engaging object, participation and action via a context-specific endeavour. It’s an emergent thought exactly without that specific intention that Q.Y.Z. is always disappointed about. But if it’s 涌现 yǒngxiàn, as H.J.Y. prefers to call it, it’s etymologically happening in large numbers, and maybe that’s something to think about. Big time, baby, big time.

Images taken from a ritual for hair-tossed-to-compost, May 2011

Images taken from a ritual for hair-tossed-to-compost, May 2011 时间 posted on: 15 May 2011 |

时间 posted on: 15 May 2011 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

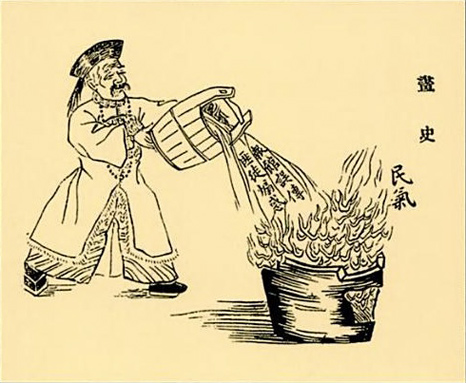

分类 filed under:  The press was seen as a tool, a transmission belt for public opinion, a marketplace of ideas. It was the platform for public discussion of issues of local as well as national importance. Hence the Chinese government “is well advised to consult public opinion” through newspapers. Pictorial evidence from November 1907 ironically underlines this point. A huge pot is filled with a burning substance labeled 舆论 yulun, “public opinion.” The characters on the lid read: “The power is with the court.” It is apparent, however, that the fire inside the pot will not easily be controlled. Public opinion seethes visibly in spit of attempts to “put a lid on it”: clouds of smoke and flames escape not just through the gap between the pot and the lid but also from a hole at the bottom. [

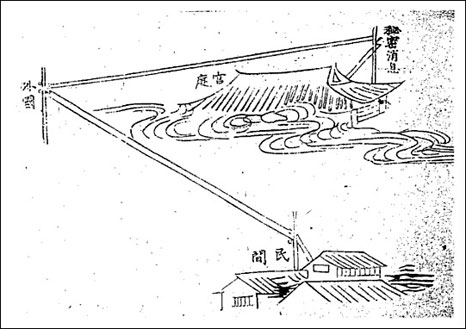

The press was seen as a tool, a transmission belt for public opinion, a marketplace of ideas. It was the platform for public discussion of issues of local as well as national importance. Hence the Chinese government “is well advised to consult public opinion” through newspapers. Pictorial evidence from November 1907 ironically underlines this point. A huge pot is filled with a burning substance labeled 舆论 yulun, “public opinion.” The characters on the lid read: “The power is with the court.” It is apparent, however, that the fire inside the pot will not easily be controlled. Public opinion seethes visibly in spit of attempts to “put a lid on it”: clouds of smoke and flames escape not just through the gap between the pot and the lid but also from a hole at the bottom. [ A cartoon that appeared in the 申报 Shenbao in October 1907 depicts the role of that alien medium, the newspaper: the caricature shows two buildings, an elaborate one labeled 宫庭 gongting, “the court,” and a much simpler one named 民间 minjian, “the people.” From the court, 秘密消息 mimixiaoxi, “the secret news,” is being transferred by telegraph to the people–but not directly. The node at which the telegraph line from the court and that leading to the people meet is labeled 外国 waiguo, “the West”. This image echoes a declaration made by the Shenbao in its first issue: “新闻纸之制疮自西人搏舆中土 The making of newspapers has been transmitted by Westerners to Chinese lands”. [

A cartoon that appeared in the 申报 Shenbao in October 1907 depicts the role of that alien medium, the newspaper: the caricature shows two buildings, an elaborate one labeled 宫庭 gongting, “the court,” and a much simpler one named 民间 minjian, “the people.” From the court, 秘密消息 mimixiaoxi, “the secret news,” is being transferred by telegraph to the people–but not directly. The node at which the telegraph line from the court and that leading to the people meet is labeled 外国 waiguo, “the West”. This image echoes a declaration made by the Shenbao in its first issue: “新闻纸之制疮自西人搏舆中土 The making of newspapers has been transmitted by Westerners to Chinese lands”. [