Happy Friends met on a sultry Sunday afternoon in Ritan Park, Beijing. There were two parts to our meeting. The first was a recapitulation of the book The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein (2007). It is a long and thoroughly investigative book, so the below summary is simply a tracing of some points in its narrative that will hopefully give and idea what it’s about and just maybe inspire some to find a copy of the book.

The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein

“This book is a challenge to the central and most cherished claim in the official story—that the triumph of deregulated capitalism has been born of freedom, that unfettered free markets go hand in hand with democracy. Instead, I will show that this fundamentalist form of capitalism has consistently been midwifed by the most brutal forms of coercion, inflicted on the collective body politic as well as on countless individual bodies.” p. 18

The beginning of shock therapies

Ewen Cameron was a psychiatrist at McGill University in Montréal, whose radical research on various experimental “treatments” (including shock therapy, extreme isolation, audio and light effects, and use of a huge variety of drugs) on unwitting mental patients was being secretly funded by the CIA. The effect of these treatments (and probably the intention) was not to cure but to create docile subjects; not to fix but to wipe away and start new (a metaphor commonly used by free market deregulation enthusiasts).

As a parallel to therapeutic work, these methods produced a set of conditions and instructions on how to terrify, disorient and infantilize, literally constructing a guide later used by military and para-military interrogators. However, it has been shown such approaches aren’t really effective in producing dependable information, but as forms of state terror.

“From Chile to China to Iraq, torture has been a silent partner in the global free-market crusade. But torture is more than a tool used to enforce unwanted policies on rebellious peoples; it is also a metaphor of the shock doctrine’s underlying logic.” p. 15

What is the Chicago School?

The University of Chicago Economics department under the leadership of Milton Friedman in the 1950s, with Friedman going on to become one of the most influential economist of the 20th Century.

“Where Cameron dreamed of returning the human mind to that pristine state, Friedman dreamed of depatterning societies, of returning them to a state of pure capitalism, cleansed of all interruptions—government regulations, trade barriers and entrenched interests.” p. 50

Friedman dreamed of a pure capitalism, stripped of all its “distortions”, like a force of nature.

“the policy trinity—the elimination of the public sphere, total liberation for corporations and skeletal social spending” p. 15

Contrast this to the at-the-time more popular models among many other post-war countries. “Chicagoans did not see Marxism as their true enemy. The real source of the trouble was to be found in the ideas of the Keynesians in the United States, the social democrats in Europe and the developmentalists in what was then called the Third World.” p. 53 (Keynesianism’s basic premise was that “countries in severe economic recession should spend money to stimulate the economy” p. 145).

On the Developmentalist trends in South America:

“The extraordinary rise of developmentalism meant that the area was a cacophony of precisely the policies that the Chicago School considered distortions or “uneconomic ideas.”” … “These were believers not in a Utopia but in a mixed economy, to Chicago eyes an ugly hodgepodge of capitalism for the manufacture and distribution of consumer products, socialism in education, state ownership for essentials like water services, and all kinds of laws designed to temper the extremes of capitalism.” p. 53

And Developmentalism, not only insulting to the Chicago School purists, was not appreciated by the American corporations with stakes in countries where this trend was growing, and with close ties to US Adminstrations. When the chance came in Chile to experiment with an economic context “wiped clear” of governmental obstacles, Friedman was a champion of measures such as spontaneous mass-scale firing, privatization, deregulation and elimination of job security, and downplayed the political repression, which was often facilitated by American interventions, by the CIA and others.

But contrary to the hands-off rhetoric, the freeing of the markets had to be done in coercive fashion, because the chaos of currencies they created, the raising of prices of basic necessities, the instability and lack of social security they demanded, and the flight of capital to foreign corporations would generally not be accepted by a democratically engaged public.

“Chile’s coup, when it finally came, would feature three distinct forms of shock, a recipe that would be duplicated in neighboring countries and would reemerge, three decades later, in Iraq. The shock of the coup itself was immediately followed by two additional forms of shock. One was Milton Friedman’s capitalist “shock treatment,” a technique in which hundreds of Latin American economists had by now been trained at the University of Chicago and its various franchise institutions. The other was Ewen Cameron’s shock, drug and sensory deprivation research, now codified as torture techniques in the Kubark manual and disseminated through extensive CIA training programs for Latin American police and military.” p. 71

The shock doctrine, then, is that disaster, war and shock are very useful for promoting large-scale economic changes in pursuit of this elusive “pure state” of the free market. Klein goes on to provide dozens of case studies in which the Chicago School policies were implemented by force or trickery in countries outside the United States, from Argentina and much of South America (where political repression resulted in thousands disappeared and assassinated), to Poland (in which a democracy newly formed from the breaking up of the Soviet Union was forced by massive debt to accept privatization conditions by the IMF, a recurring theme) and Russia (in which overnight privatization and handouts by Yeltsin’s government resulted in huge, unchecked concentrations of wealth and glut of poverty) to China (whose liberalization of the market disproved any theories of consequential political liberalization) and Southeast Asia (results of economic crash), as well as the UK and United States (Thatcher and Reagan) and elsewhere.

“In Russia the billionaire private players in the alliance are called “the oligarchs”; in China, “the princelings”; in Chile, “the piranhas”; in the U.S., the Bush-Cheney campaign “Pioneers.” Far from freeing the market from the state, these political and corporate elites have simply merged, trading favors to secure the right to appropriate precious resources previously held in the public domain—from Russia’s oil fields, to China’s collective lands, to the no-bid reconstruction contracts for work in Iraq.” p. 15

“As I dug deeper into the history of how this market model had swept the globe, however, I discovered that the idea of exploiting crisis and disaster has been the modus operandi of Milton Friedman’s movement from the very beginning—this fundamentalist form of capitalism has always needed disasters to advance.” p. 9

How these processes are “legitimately,” systemically spread is in cases of disasters or political upheaval and regime change, where a country is in need of help and the aid funding bodies (IMF, World Bank) mandate vast, swift Chicago-School-style changes to economic policies in order to release funds, but they are also done by a government on its own people (for example in China).

“In China in n-i-n-e-t-e-e-n-e-i-g-h-t-y-n-i-n-e, it was the shock of the T-A-M S-q-u-a-r-e m-a-s-s-a-c-r-e and the subsequent arrests of tens of thousands that freed the hand of the Communist Party to convert much of the country into a sprawling export zone, staffed with workers too terrified to demand their rights.” p. 10

As the spread of Neoliberal economic reforms exhausted possible developing countries, post-socialist states or changed regimes to exploit, it seemed to be facing its own limits.

“In retrospect, it is striking that capitalism’s monopoly period, when it no longer had to deal with competing ideas or counterpowers, was extremely brief—only eight years, from the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 to the collapse of the WTO talks in 1999. But rising opposition would not slow the determination to advance this extraordinarily profitable agenda; its advocates would simply ride the waves of fear and disorientation created by bigger shocks than ever before.” p. 280

One of the bigger shocks Klein refers to is the timely beginning of the second Iraq war, where the disaster capitalism process took another turn, with the Chicago School ideology dismantling the State itself from the inside. Consequently, it was very good for business. “Hollow Government,” the goal of Rumsfeld, Cheney, and a host of other Bush administration figures, means that the government sheds many of its previously core responsibilities and basically call on corporations for disaster response, war-fighting, defense, as well as the many secondary support industries.

“It was a move that brought the shock doctrine to a new, self-referential phase: until that point, disasters and crises had been harnessed to push through radical privatization plans after the fact, but the institutions that had the power both to create and respond to cataclysmic events—the military, the CIA, the Red Cross, the UN, emergency “first responders”—had been some of the last bastions of public control. Now, with the core set to be devoured, the crisis-exploiting methods that had been honed over the previous three decades would be used to leverage the privatization of the infrastructure of disaster creation and disaster response. Friedman’s crisis theory was going postmodern.” p. 288

“Although the stated goal was fighting terrorism, the effect was the creation of the disaster capitalism complex—a full-fledged new economy in homeland security, privatized war and disaster reconstruction tasked with nothing less than building and running a privatized security state, both at home and abroad. The economic stimulus of this sweeping initiative proved enough to pick up the slack where globalization and the dot-com booms had left off. Just as the Internet had launched the dot-com bubble, 9/11 launched the disaster capitalism bubble.” p. 299

“The role of the government in this unending war is not that of an administrator managing a network of contractors but of a deep-pocketed venture capitalist, both providing its seed money for the complex’s creation and becoming the biggest customer for its new services. ” p. 12

In this new order, Klein claims that where before there used to be an unspoken “revolving door” between government and industry, the corporatist state has installed an archway between governments and corporations. (list on p. 315) Many US politicians (and Israelis, ch. 21) have direct investment in the defense industry, and therefore have an interest in prolonging the endless cycle of destruction, fighting and reconstruction.

Klein sees hope in newer developments, such as the return of a social awareness and sense of control to areas of the former Southern Cone (South America), some 20 or 30 years after the fact. Getting over the shock is a matter of time, but also of being given the ability to reconstruct on their own, without the intervention of multi-national corporations providing ready-made and usually inadequate and indifferent solutions at a profit.

“Such people’s reconstruction efforts represent the antithesis of the disaster capitalism complex’s ethos, with its perpetual quest for clean sheets and blank slates on which to build model states. Like Latin America’s farm and factory co-ops, they are inherently improvisational, making do with whoever is left behind and whatever rusty tools have not been swept away, broken or stolen. Unlike the fantasy of the Rapture, the apocalyptic erasure that allows the ethereal escape of true believers, local people’s renewal movements begin from the premise that there is no escape from the substantial messes we have created and that there has already been enough erasure—of history, of culture, of memory. These are movements that do not seek to start from scratch but rather from scrap, from the rubble that is all around. As the corporatist crusade continues its violent decline, turning up the shock dial to blast through the mounting resistance it encounters, these projects point a way forward between fundamentalisms. Radical only in their intense practicality, rooted in the communities where they live, these men and women see themselves as mere repair people, taking what’s there and fixing it, reinforcing it, making it better and more equal. Most of all, they are building in resilience—for when the next shock hits.” p. 466

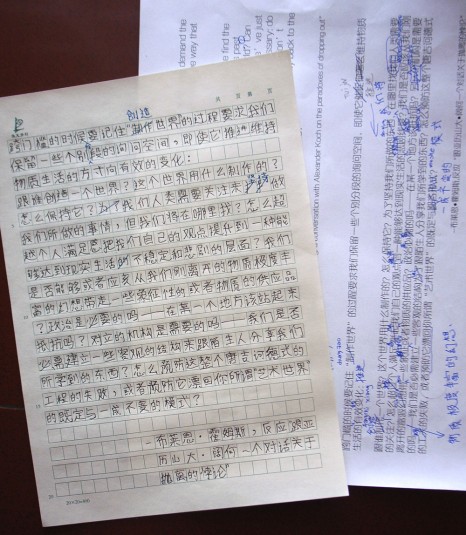

After 450 pages of tales of disaster, exploitation and domination, such a conclusion might appear defensive and make-do, rather than a way to end the cycle. Our discussion in Part 2 of the Happy Friends meeting on June 20th was an elaboration of this theme of where there might be hope, in light of the atomization of groups and spaces, and with reference to the text “N-i-n-e-t-e-e-n-e-i-g-h-t-y-n-i-n-e and the historical roots of neoliberalism” by Wang Hui (2004). Appearing soon…

The press was seen as a tool, a transmission belt for public opinion, a marketplace of ideas. It was the platform for public discussion of issues of local as well as national importance. Hence the Chinese government “is well advised to consult public opinion” through newspapers. Pictorial evidence from November 1907 ironically underlines this point. A huge pot is filled with a burning substance labeled 舆论 yulun, “public opinion.” The characters on the lid read: “The power is with the court.” It is apparent, however, that the fire inside the pot will not easily be controlled. Public opinion seethes visibly in spit of attempts to “put a lid on it”: clouds of smoke and flames escape not just through the gap between the pot and the lid but also from a hole at the bottom. [p. 16]

A cartoon that appeared in the 申报 Shenbao in October 1907 depicts the role of that alien medium, the newspaper: the caricature shows two buildings, an elaborate one labeled 宫庭 gongting, “the court,” and a much simpler one named 民间 minjian, “the people.” From the court, 秘密消息 mimixiaoxi, “the secret news,” is being transferred by telegraph to the people–but not directly. The node at which the telegraph line from the court and that leading to the people meet is labeled 外国 waiguo, “the West”. This image echoes a declaration made by the Shenbao in its first issue: “新闻纸之制疮自西人搏舆中土 The making of newspapers has been transmitted by Westerners to Chinese lands”. [p. 23-24]

时间 posted on: 9 May 2011 |

时间 posted on: 9 May 2011 |  发布者 author:

发布者 author:

分类 filed under:

分类 filed under: